From the littered overbuilt shores of Corfu lots of people still reap perfect images of the island landscape that so enchanted those who passed through before mass tourism – the monastery of Panagia Vlacherna and Pontikonissi omitting the roar of the airport and the multistoried hotel on Kanoni, the pretty sight of Gouvina Cove where you can park by the road a few hundred metres from the end of the dual carriageway at Tzavros, and a small crop with photoshop can easily disappear the cloned boxes and concrete skeletons that disfigure Barbati, and from a distance even the jutting hull of the Nissaki Beach Hotel can be blended into the towering cliffs of Pantocrator, though ignoring 'Seashore Villas' plonked on what was once the village of Ag Spiridon near the car-blocked streets of Kassiopi is a little trickier, but removing the endless plastic detritus from the beaches needs no army of earnest litter-pickers - just a tiny upward shift of the lens records the sublime landscape of archetypal Greece above the sparkling blue of the Kerkyra Sea, as from the dizzy heights of Angelokastro the cliffs of Capes Iliodoros and Plaka facing the Adriatic horizon distract from the disastrous shamble of Paleocastritsa.

It was the better-off who recorded their memories of Corfu’s charms; incubating their future commodification. For peasants, fishermen, small shopkeepers, beauty lay in health and harvest; the two connected. Once upon a time, when people gazed longingly at the green island from the rocky mainland of Epirus they saw its wealth not in its landscape but its fecundity, as a family judging a prospective daughter-in-law might rate child-bearing hips, above a pretty face [Of these observations Jim Potts remarks: 'Succinctly stated. But I sincerely believe that even the poorest peasants appreciated Corfu's natural beauty and recorded it in their own ways, through orally-transmitted tales, folksongs and proverbs, for instance. Is it not possible to feel a sense of profound regret, even while cutting down olive trees to build a better house or to make some money to pay to educate one's children? The sense of regret increases with time.']

Only in the last fifty years has Corfu’s harvest changed from what grew here to what disembarked from ships and planes. The shift in wealth that followed – from the grand farm estates of the nobility - the signorini - thriving and then just surviving on the close cropping of tenant labour - needed and got little help from government. Oil in Arabia and Texas turned arid scrubland into gold. Tourism in Corfu made hard-worked seaside estancias into cornucopias. Sea, sand and gravel were already here. Cement made new byres, the digger and the dozer swiftly cleared the island curtilage of unnecessary trees. An olive grove or a vineyard anywhere on the island sprouting concrete in place of roots could send your children to university and show a way, other than emigration, to escape a life of sweated labour, as a fibreglass boat with a glass bottom over one busy summer could replace the hazards and uncertainty of fishing round the year. Landscape enjoyed by those with the means to gaze upon it, that had inspired painting and poetry became publicity and copy to attract the new wealth of millions.

I hear myself muttering “You make all this sound like a bad thing”

“Well yes and no” I reply “Yes and no”

The noble leftwinger Lord Bertrand Russell remarked that ‘the central dilemma of socialism is that you can ruin anything by making it available to everybody’.

“If only governments instead of being bought by the Lopachin's so excited about laying an axe to Corfu’s cherry orchards had pursued a research based policy that had regulated the massive changes brought by mass tourism; created an infrastructure that was less piecemeal and opportunistic”

A broad smile grows on my face at my naïve pomposity.

“Έλα τώρα! Surely you jest?” I exclaim “Weren’t these messy changes always going to be irresistible, any attempt at planning overwhelmed not just by greased palms and brown envelopes but by human yearning. Try testing your commitment to properly regulated planned development of tourist infrastructure against another lifetime of horizon-less poverty heaped on the deprivation of centuries”

The challenge of Ano Korakiana; a few years back – three or four at most – there was a discussion, probably one of those animated debates in which I’ve sat in the back nodding sagely as though my Greek is good enough to follow the arguments, in which villagers, in large numbers explored whether they should have a taverna or indeed any other commercial establishment in the village that catered for and attracted foreign visitors. I first heard of this meeting from two British neighbours in the crowd awaiting midnight the Easter Saturday before last

“They decided, on balance” said Wesley “that they would not.”

This confirmed the presumption I heard a few years earlier when we were planning to buy a house in the village that “Ano Korakiana doesn’t welcome tourists.”

To suggest that Ano Korakianas do not welcome strangers – for all those 44 voting last Sunday for Golden Dawn to keep foreigners out of Greece – would be slander.

Apart from the fact that an overwhelming majority of eligible voters here voted for the left including the KKE (third in the poll here), this village is nothing if not hospitable, not just to people who have made their lives here but to passing tourists on foot, on cycles and in cars, who stop to look about, sometimes puzzled as to where to buy a drink or a meal. Such people are sometimes treated to these; as guests, not customers.

So? So what makes this village? What makes any village? It’s a question elaborated across the world. I have urgent thoughts on this, I feel a need to know and understand. This village has a website, as with all Greek villages - a global diaspora, an historian, a documented history that goes back over a 1000 years...

...and a permanent population that qualifies it as a working village in the eyes of government. It has a medical centre staffed at different times through the week, and of course it has the Spyros Samaras Philharmonic Society of Korakiana, including its superlative band that performs here, in Corfu Town and across Greece, with practise rooms (a new finely restored band-room higher in the village will probably be ready next year), instruments, uniforms and regular rehearsals – an institution linked to a choir and dancers – who rehearse and learn in both the band-room on Democracy Street and in the Agricultural Co-op which also processes olive oil; providing space for meetings and village celebrations like Carnival through the year. It has 35 churches – the one’s most used Ag Georgios, Ag.Spiridon, Ag. Athannasios, Ag. Isadorus. I can’t list all their names though they are described in Kostas Apergis' history – but also the semi-ruined Prophet Elias...

...marking the ancient village boundary on the hill a mile away and Ag.Paraskevi, a church below the village. There’s a taxi service on Democracy Street - almost opposite us, and buses to and from the city. There’s a second olive processing factory below the village, a furniture making workshop, a carpentry shop, a thriving bakery serving other villages and two grocery shops on Democracy Street and a kindergarten and nursery and a kafenion - του καφενείου Κεφαλλονίτη - regularly attended, where even Linda and I have enjoyed a coffee and beer, tho' there's still a mainly male attendance there overseen by Maria, its proprietor. Another kafeneon - John Laschari's, Γιάννη Λάσκαρη, ceased in 2007.

The village primary school closed last year and is to be replaced by a special school serving the whole island. Ano Korakiana appears to have a museum for an exceptionally gifted village sculptor who worked in the first part of the 20th century – but disappointingly, this though full of invisible sculpture, with parking spaces displaying signs saying it’s a museum, is, I’m authoritatively assured, never open (but see this - in early 2014 also this about the village sculptor Aristeidis Metallinos). There is another business – Luna D’Argento – a kilometre below the village, a venue for weddings and dances, also occasionally for the whole village as at the cutting of the New Year Cake, Vassilopita, and next to that a stable for horse trekking and riding lessons run by our friend Sally.

I couldn’t attest to how many other skills and talents are exercised in Ano Korakiana. There are people who in repairing or rebuilding parts of their houses are conscientious about maintaining its architectural character – what experts sometimes call 'vernacular'. (Example 1 ~ Nick and Sophia's house. Example 2: George Poplis's work and Sally and Mark's house - scroll down. Example 3: The restored Music School). Our house lost some of this vernacular at the hands of an English builder hired by the previous English owners who destroyed its balcony and steps, replaced by us via the admired skills and taste of Alan Barrett of Ag Markos.

There are doctors, pharmacists, house-painters, plasterers, carpenters, artists, probably writers preferring anonymity, many wine makers, woodcutters preparing a delivering fuel, gardeners cultivating vines and vegetables, gardeners growing a festival of flowers – geranium, roses, honeysuckle, jasmine, bourgainvillea, wisteria, cana and arum lilies; a few farmers tending larger fields, small vineyards, keeping sheep and goats, chicken, turkey, guinea fowl, ducks and geese and of course harvesting olive oil from their olive groves - the island’s most distinctive crop; plumbers and mechanics and builders, roofers, private tutors teaching English and other skills; engineers, accountants working in the city. Kostas is the village priest. Ano Korakiana fields a football team that triumphs across Corfu and beyond, but hopes of having a local football field - one a quarter completed that has sat fallow below the village for over a decade - seem to have expired. This is made less problematic by the existence of two pitches finely maintained that Ano Korakiana can share with its neighbour Skripero, sited close to the T-junction between the winding south-westward lane out of Ano Korakiana where it meets the road to Sidari.

Ano Korakiana has organization. It has committees for the band, shareholders for the Co-op. It has government. It debates and makes decisions – με δημοκρατικό τρόπο - about events and direction. Some say it has the best water on the island. Does all this make ‘a village’; in modern parlance – a sustainable community?

It was the better-off who recorded their memories of Corfu’s charms; incubating their future commodification. For peasants, fishermen, small shopkeepers, beauty lay in health and harvest; the two connected. Once upon a time, when people gazed longingly at the green island from the rocky mainland of Epirus they saw its wealth not in its landscape but its fecundity, as a family judging a prospective daughter-in-law might rate child-bearing hips, above a pretty face [Of these observations Jim Potts remarks: 'Succinctly stated. But I sincerely believe that even the poorest peasants appreciated Corfu's natural beauty and recorded it in their own ways, through orally-transmitted tales, folksongs and proverbs, for instance. Is it not possible to feel a sense of profound regret, even while cutting down olive trees to build a better house or to make some money to pay to educate one's children? The sense of regret increases with time.']

Only in the last fifty years has Corfu’s harvest changed from what grew here to what disembarked from ships and planes. The shift in wealth that followed – from the grand farm estates of the nobility - the signorini - thriving and then just surviving on the close cropping of tenant labour - needed and got little help from government. Oil in Arabia and Texas turned arid scrubland into gold. Tourism in Corfu made hard-worked seaside estancias into cornucopias. Sea, sand and gravel were already here. Cement made new byres, the digger and the dozer swiftly cleared the island curtilage of unnecessary trees. An olive grove or a vineyard anywhere on the island sprouting concrete in place of roots could send your children to university and show a way, other than emigration, to escape a life of sweated labour, as a fibreglass boat with a glass bottom over one busy summer could replace the hazards and uncertainty of fishing round the year. Landscape enjoyed by those with the means to gaze upon it, that had inspired painting and poetry became publicity and copy to attract the new wealth of millions.

I hear myself muttering “You make all this sound like a bad thing”

“Well yes and no” I reply “Yes and no”

The noble leftwinger Lord Bertrand Russell remarked that ‘the central dilemma of socialism is that you can ruin anything by making it available to everybody’.

“If only governments instead of being bought by the Lopachin's so excited about laying an axe to Corfu’s cherry orchards had pursued a research based policy that had regulated the massive changes brought by mass tourism; created an infrastructure that was less piecemeal and opportunistic”

A broad smile grows on my face at my naïve pomposity.

“Έλα τώρα! Surely you jest?” I exclaim “Weren’t these messy changes always going to be irresistible, any attempt at planning overwhelmed not just by greased palms and brown envelopes but by human yearning. Try testing your commitment to properly regulated planned development of tourist infrastructure against another lifetime of horizon-less poverty heaped on the deprivation of centuries”

|

| Linda and our friend Jill on the Kato road to Ano Korakiana |

“They decided, on balance” said Wesley “that they would not.”

This confirmed the presumption I heard a few years earlier when we were planning to buy a house in the village that “Ano Korakiana doesn’t welcome tourists.”

To suggest that Ano Korakianas do not welcome strangers – for all those 44 voting last Sunday for Golden Dawn to keep foreigners out of Greece – would be slander.

|

| Το πάρτυ του Σάϊμον |

So? So what makes this village? What makes any village? It’s a question elaborated across the world. I have urgent thoughts on this, I feel a need to know and understand. This village has a website, as with all Greek villages - a global diaspora, an historian, a documented history that goes back over a 1000 years...

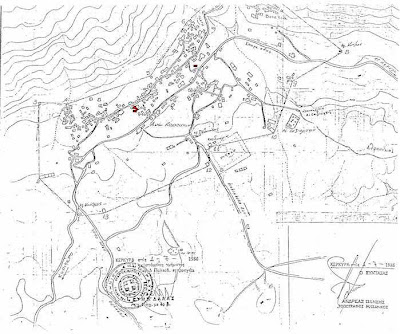

|

| Kostas Apergis' history of Ano Korakiana |

|

| Church of the Prophet Elias before mother Greece |

The village primary school closed last year and is to be replaced by a special school serving the whole island. Ano Korakiana appears to have a museum for an exceptionally gifted village sculptor who worked in the first part of the 20th century – but disappointingly, this though full of invisible sculpture, with parking spaces displaying signs saying it’s a museum, is, I’m authoritatively assured, never open (but see this - in early 2014 also this about the village sculptor Aristeidis Metallinos). There is another business – Luna D’Argento – a kilometre below the village, a venue for weddings and dances, also occasionally for the whole village as at the cutting of the New Year Cake, Vassilopita, and next to that a stable for horse trekking and riding lessons run by our friend Sally.

I couldn’t attest to how many other skills and talents are exercised in Ano Korakiana. There are people who in repairing or rebuilding parts of their houses are conscientious about maintaining its architectural character – what experts sometimes call 'vernacular'. (Example 1 ~ Nick and Sophia's house. Example 2: George Poplis's work and Sally and Mark's house - scroll down. Example 3: The restored Music School). Our house lost some of this vernacular at the hands of an English builder hired by the previous English owners who destroyed its balcony and steps, replaced by us via the admired skills and taste of Alan Barrett of Ag Markos.

There are doctors, pharmacists, house-painters, plasterers, carpenters, artists, probably writers preferring anonymity, many wine makers, woodcutters preparing a delivering fuel, gardeners cultivating vines and vegetables, gardeners growing a festival of flowers – geranium, roses, honeysuckle, jasmine, bourgainvillea, wisteria, cana and arum lilies; a few farmers tending larger fields, small vineyards, keeping sheep and goats, chicken, turkey, guinea fowl, ducks and geese and of course harvesting olive oil from their olive groves - the island’s most distinctive crop; plumbers and mechanics and builders, roofers, private tutors teaching English and other skills; engineers, accountants working in the city. Kostas is the village priest. Ano Korakiana fields a football team that triumphs across Corfu and beyond, but hopes of having a local football field - one a quarter completed that has sat fallow below the village for over a decade - seem to have expired. This is made less problematic by the existence of two pitches finely maintained that Ano Korakiana can share with its neighbour Skripero, sited close to the T-junction between the winding south-westward lane out of Ano Korakiana where it meets the road to Sidari.

Ano Korakiana has organization. It has committees for the band, shareholders for the Co-op. It has government. It debates and makes decisions – με δημοκρατικό τρόπο - about events and direction. Some say it has the best water on the island. Does all this make ‘a village’; in modern parlance – a sustainable community?

[A cautionary essay on the village in England, Bagnor, where I grew up between 1949-1960 - translated. and posted on Ano Korakiana's website..Νομίζεις, ότι κάποιοι από εμάς θέτουμε σε κίνδυνο αυτό που αποκαλείται «ακεραιότητα» της Άνω Κορακιάνας; Είναι δυνατόν οποιοιδήποτε από μας (προσπαθώ να αποφύγω το «εμείς» επειδή εσείς και εγώ και οι συγγενείς μας είναι μοναδικοί και δεν θέλω να μας χαρακτηρίσω όλους μαζί ως «αλλοδαπούς») να επικριθούμε για τις επιλογές μας στη ζωή; Δεν θα επιθυμούσα η Άνω Κορακιάνα να γίνει όπως η μη-κοινότητα του Μπαρμπάτι, με τα νεόκτιστα σπίτια και τη θαυμάσια θέα προς τη θάλασσα, που κατοικείται όμως αποκλειστικά από εποχιακούς επισκέπτες. Ελπίζω ότι νέοι Έλληνες γεννημένοι στην Άνω Κορακιάνα θα είναι σε θέση να μείνουν, ή εάν φύγουν, θα επιστρέψουν για να συμβάλουν στη ζωή του χωριού. Υπάρχουν χωριά στην Αγγλία που παρότι έχουν μετασχηματιστεί, εν τούτοις έχουν οδηγηθεί σε μια νέα ισορροπία, με σημαντική συμμετοχή σε αυτό, των σχετικά νεοφερμένων, που έχουν βρει την αρμονία τους με τους εναπομείναντες παλαιούς κατοίκους και πίεσαν για το κτίσιμο «φτηνής στέγης» ώστε νεότεροι άνθρωποι να μπορούν να παραμείνουν στο χωριό...]

|

| Ano Korakiana |

...and some thoughts from an earlier entry in Democracy Street which draw on the experiences of Geert Mak in Jorwert - reported beautifully but without the 'aren't they quaint and eccentric and charming' tropes of some commentators on villages

(from a review)...The point is made, and reinforced by research carried out by others around the world that villages divided by space and time have more in common with each other, than they do with their nearest urban neighbour. Villagers are proud of the small differences. Jorwert is very special to Jorwerters. They are proud of tradition, and cling on to the facets of it that survive the changes in technology and bureaucracy as best they can. They believe in the future and in the family. And that is what the country, and therefore the village, life is all about. It is not about being an individual. It is not about making money or acquiring stuff . It is all about survival. Making sure that what is outlives you, and that your children are there to take it on and take it forward and protect it as you have done. This is true of every village, everywhere. What is also true of every village in northern Europe is that since the end of the second world war, the local people have had to cope with the Europisation of regulation. The disaster of the Common Agricultural Policy played out with the best of intentions and the worst of results. This is as true for the dairy farmers around Jorwert as it is for the sheep farmers of Wales. The lure of education, of easy money, of city life and hedonism affected the children of Jorwert, just as it did those of the French mountain youngsters or those in the Spanish plains. Schools struggled and then closed. Shops followed them. Churches remained the focus, but in protestant northern Europe they didn't have the hold they had in the catholic south – which isn't to say the whole Jorwert didn't put aside their personal faiths the day the church tower collapsed and set about figuring out how to rebuild it! Mak examines all of the issues in true journalistic fashion, supporting his arguments with academic study and local example...*** *** ***

Our bathroom washbasin had a mixer tap with a spout coming out so far it splashed the floor. I assembled the new tap I’d bought from Niko at Tzavros, fixing flexible pipes to hot and cold, inserting the spout into the base. With new found skills I removed the old tap, groping below the drips with a bottle spanner, and fitted the new. It leaked hot and cold unless you screwed the taps so tight Lin could hardly turn them on again. I took it back. Nico changed the tapwashers, clearly damaged by the tightened taps. He even added a new valve unit to the cold. Back in place the problem was worse. Hot water went on running however tight the tap. Cold water was a trickle with tap full on. Back to Nico. He was puzzled. Began to think about replacing both valve units, then, examining the unit more, he noticed I’d pushed the spout too far into the mixer unit. Removing one tap showed the spout base intruding into the core of the unit.

“So it was my fault”

“But an easy mistake” said Nico generously.

He tried to pull out the spout. We both tried to pull it out; he on one side of the counter, I on the other. Another customer came in and saw us struggling.

“Κράτει! Whoa! What’s the problem?”

“We can’t get these two apart!” I said offering him the spout. Another tug-of-war with he and I risking falling over had the parts separated. Then Nikos and his customer tried - younger men more powerfully leaning back - bracing and hauling at the unit. No movement.

“We must apply a flame” said Nikos and lit a blow lamp “OK?” he asked.

I nodded

“Στάσου. Just one more thing first” said Nico and unscrewed the second valve unit. Again we prepared to tug, but the spout came clear with ease.

“Bravo!” We raised our arms in shared triumph

“The problems of the world are sorted!”

Back home the reassembled taps worked perfectly. Nico would take nothing from me.

There's an important book here.

ReplyDeleteDisseminate widely!

"It was the better-off who recorded their memories of Corfu’s charms; incubating their future commodification"

ReplyDeleteSuccinctly stated. But I sincerely believe that even the poorest peasants appreciated Corfu's natural beauty and recorded it in their own ways, through orally-transmitted tales, folksongs and proverbs, for instance. Is it not possible to feel a sense of profound regret, even while cutting down olive trees to build a better house or to make some money to pay to educate one's children? The sense of regret increases with time.

Yes! This is why any more serious account than mine of what has happened should take in a wider spectrum. I've gone for polemic, used to the adversarial style of debate on which I was schooled. Few things are black and white, and my own ignorance doesn't help. The 'orally-transmitted tales, folksongs and proverbs' to which you refer, not to mention dances and detailed celebrations and rituals, were things I'd not thought of. Thanks Jim, for enriching my understanding and judgement. I am still much exercised by the passion in Maria's Pimping of Panorea but their's a more compassionate mix of moral colour in her novel about Marnee.

ReplyDeleteSometimes a sincere, passionate cry of despair is what is needed to make people think more deeply about the issue?

ReplyDeleteEvocative and riveting ... read every word and even clicked on video of Icarus Airways zooming over KK. Actually felt myself redden at the thought of crass previous owners; thumbs up to alan barrett.

ReplyDeleteWas meant to be busying in town but told 'my companion' (as is the correct term these days) that i was taking my time to read the whole piece. she reads over my shoulder so's to jab elbow and hurry me along. she reaches section about 'thriving bakery ... two grocery shops on Democracy Street ... kafenion ...'

"How come they're so fussy? she asks. How come "*even* Linda and I have enjoyed a coffee and beer?"

I ignore Ms Unanswerable-who-must-get-into-town. My eye is elsewhere, much exercised by SB's cobbled "their's" reference to Marnee's compassionate mix.

Well-crafted thought-provoking piece on both what makes a village *and* what makes a good ... what? resident? implant? my mother was one, SB is another. Me, alas, not so good.

Hm? Generous. On your last point - I guess we going to and fro might be flotsam, whereas as you -staying - qualify as jetsam

DeleteKafenion is guarded by Maria from women interlopers - but via Greek friends we managed an entry. And Maria once the ice was broken is full of philometo. (Hence 'even')

ReplyDeleteIn fact it's Mamee, not Marnee...never mind.

ReplyDeleteTypos are hard to avoid, even in such a brilliant piece!

I'm beginning to think of imagining our village through the eyes of one of the cats that share our space in it. It was a lovely device of Maria's - for continuity but also to create a perspective that got round human judgement.

ReplyDeleteHello! I just found this and am looking forward to reading all of this and digesting it slowly. I will be moving with my young family to Ano Korakiana for a year starting this summer, and we are getting very excited. For us this is dream come true and it looks like from your picture we may be neighbours (we are renting a house nearby it looks like). My father is from the village and though we are thoroughly Canadian we are excited about connecting with my roots. Any tips or advice is very welcome!! Cheers!

ReplyDeleteThe name Martzoukos is well known and recorded in Ano Korakiana. The name is carved - in initials - on a door in our home on Democracy Street:

ReplyDeletehttp://democracystreet.blogspot.co.uk/2008/04/book-15-18-by.html

I look forward to meeting you.