The Ottoman Empire, Rumelia and the Septinsular Republic

The human geography is confusing. Rumelia, Djezair, Wallachia, Anatolia, Cyrenaica? Names of places keep shifting, appearing in different versions, different languages. From secondary sources - mainly the web - I know that over four centuries the Venetians ruled Corfu and the six other Ionian islands - Corfu especially on the front-line between Imperial Ottoman Islam and Christian Europe - then for two years at the end of the 18th century, the islands, taken from Venice as part of Napoleon's rearrangement of Europe, became the French Departements Mer-Égée, Ithaque et Corcyre. Revolutionary jubilation suffused the population as the privileges of the island's Venetian aristocracy were abolished, but taxation of Corfiots and ill-discipline among the French soldiery soured relations.

Just before Christmas 1798 Admiral Ushakov with a joint Russian-Ottoman fleet besieged the garrison at Corfu. Despite extra fortifications, the French surrendered in March 1799. In 1800 the seven islands were declared the Septinsular Republic, a tributary state of Sultan Mahmud II - the closest the Turks ever got to ruling Corfu, though the new Republic was in effect a Russian Protectorate, supported by a population of fellow Orthodox Christians - the period during which the Corfiot noble, Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, who, twenty five years later, would become president of the new republic of Greece, gained his first experience of government.

In 1807, under the Treaty of Tilsit, the French re-annexed the Ionian Islands placing them under the governorate of General Cæsar Berthier. A year later the wider European conflict brought the British soldier John Oswald to the Mediterranean, in charge of a brigade harrying the coast of French-occupied Italy and, then, in 1809 leading a force to invade the Ionian Islands capturing Zante, Ithaka, Cerigo and Cephalonia, where Oswald announced:

We present ourselves to you, Inhabitants of Cephalonia, not as Invaders, with views of conquest, but as Allies who hold forth to you the advantages of British protection.

In 1810 Oswald and Richard Church, an Anglo-Irish career soldier, invaded Santa Maura (modern Lefkada or Levkas) with a force of 2000 British and Greek soldiers, many of the latter to become fighters in the Greek War of Independence. They captured Levkas after heavy fighting. For this Oswald was made governor of the Ionian Islands, based in Zante, maintaining a British strategic presence, forming diplomatic relations with the Ottoman governors of mainland Greece. When Oswald left for England in 1811, Richard Church (later to become a General in the Greek War of Independence) succeeded. After less than a year, Church, slowly recovering from an arm wound incurred in the battle for Levkas, gave up the the governorship to George Airey, to tour through Ottoman occupied Greece as far as Constantinople.

After Napoleon's first abdication but before his return from exile in Elba and the battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815, came the Congress of Vienna at which, over eight months between November 1814 and June 1815, allied ambassadors negotiated a map of post-Napoleonic Europe. Richard Church presented a report to Congress arguing that the Ionian Islands should stay under the British flag, recommending its extension to Parga and other Greek mainland towns in the possession of Ali Pasha of Yanina.

Corfu, defended by a French garrison under General Donzelot, was ordered by Louis XVIII to surrender to Sir James Campbell. After Napoleon's final defeat and second abdication, Great Britain, Russia, Austria and Prussia under the Treaty of Paris - 9th November 1815 - agreed to place the United States of the Ionian Islands under the 'amical protection' of Great Britain, and to give Austria the right of equal commercial advantage with the protecting country, a plan strongly approved by Count Kapodistria. This arrangement reinforced by the 'Maitland constitution' of 26 August 1817, creating a federation of the seven islands, with Sir Thomas Maitland its first High Commissioner [of Maitland's rule I've more to learn, but see p.174 of this reference: 'a colossal statue' in Cephalonia, a bust by Canova in Zante, a monument in Ithaka and a 'second triumphal arch' in Santa Maura! Chap. VI of the 1821 Edinburgh Annual Register, Sir Walter Scott's ambitious and eventually failed encyclopedic project for which I'm grateful and - 16/6/09 - a comment from Paxos on my flickr posting of Maitland's signature]

Thomas Maitland, second High Commissioner

explains "the advantages of British Protection" 1819

The United States of the Ionian Islands 1817 ~ National Archives

Coach 420 on the M1 to London and the National Archives

To get more than second-hand insights I need to visit primary sources; see and carefully touch original papers, scan the gestures of official handwriting. So, I'm up at 5.30 for a day in London; cycling to Digbeth for a coach to Victoria (£9.40 return, and my folding bike in its bag accepted as luggage) then catching a District Line Underground to Kew, with a packed lunch from Lin.

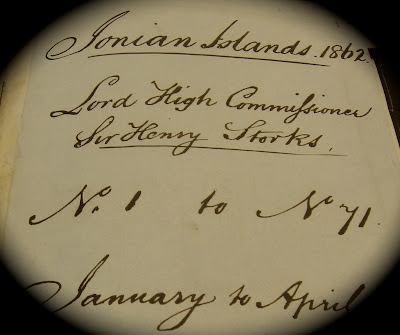

I've already learned that the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands, including Corfu, was headed by thirteen governors or rather a 'Commissioner' changed to 'Lord High Commissioners' - Sir James Campbell in 1814; half a century and twelve commissioners later, Sir Henry Storks, and overseeing the transition to union - enosis, Ένωσις - in 1864 with the Hellenic monarchy, the Greek Count Dimitrios Nikolaou Karousos [scroll down to the Ionian Islands on this link listing lead politicians and officials over the years ].

I've already learned that the British Protectorate of the Ionian Islands, including Corfu, was headed by thirteen governors or rather a 'Commissioner' changed to 'Lord High Commissioners' - Sir James Campbell in 1814; half a century and twelve commissioners later, Sir Henry Storks, and overseeing the transition to union - enosis, Ένωσις - in 1864 with the Hellenic monarchy, the Greek Count Dimitrios Nikolaou Karousos [scroll down to the Ionian Islands on this link listing lead politicians and officials over the years ]. Primary sources at The National Archives

I'm also on a long delayed errand following the letter I got from Thanassis Spingos and Kostas Apergis in Ano Korakiana in December 2007:

Dear Simon. It is said that before the Union of the Ionian Islands with Greece (1864), inhabitants of Ano Korakiana signed a 'paper' asking the British Government to keep the islands under Britain...We have been looking for this paper for years at the Greek archives without result. We wonder if you can help us by searching this paper in British archives (Parliament, Colonies archives, Foreign Office etc). We are sure that one of the names that signed the paper is Panos, Panayiotis or Panagiotis Metallinos (Μετταλινος). He was the 'leader'. A similar paper has been signed by inhabitants of Kinopiastes (another village in Corfu) and one village in Zakynthos island...When I see Kostas or Thannassis I feel embarrassed at my delay. I think I've feared not finding the document they asked me about - through lack of diligence; through not being able to read the language in which it may be couched. After five hours hefting requested books from the locker allocated me in the Reading Room to my allocated desk I'd had a fascinating dip into original sources, gaining confidence as I went along, especially as all documents in Greek or Italian have an English translation attached. Only some of the handwriting is hard to follow.

I'd arrived as an ingénue. The staff at the National Archives are pros - bright, unpatronising. The place teems with people who know their way - veteran researchers - and others, like me, there for the first time.

First step was leaving my folding bicycle and bag in a cloakroom chained 'keep your key...put your laptop and pencils - no pens - in a transparent plastic bag.' Then came the daily briefing for newbies on how to get started - 20 minutes helpful guidance; then to 'The Learning Zone', a few yards away on the same floor where a bank of helpers, screens on-line to the archives, gave hints on catalogue searching. To see Ionian Protectorate documents I'd need a reader's card. That involved five minutes being photographed and showing ID - driving licence and a utility bill. I haven't done original text research for so long, it was like going back to school, with the excitement but not the trepidation. Finally I strolled through a polite security check, swiped my new card and came to the Reading Room.

Here you check in at an enquiry counter and are allocated a triangular space on one of many circular desks. Grey polystyrene blocks for large volumes to protect book spines, little weights like necklaces, so you don't have to press pages down with your fingers, and stands for taking photos with your own or a provided camera are to hand. I was also allocated a locker with the same number as my desk space - 20C - in one of two bays of about a hundred tiered lockers; all with glass doors on the reader's side, open at the bac. As we were told at the briefing talk, you order up to three items from the catalogue, with a note over the desk and, after a bit, by sitting at a computer screen by the counter, entering your reader's number from your card and searching and ordering; the computer keeping a tally of what you've requested already. After a maximum of 40 minutes - time for a coffee downstairs - the first three volumes had been placed in my locker. I could take them, one at a time, to study at my desk space, having ordered the next three items. By the time I'd looked through the first three, the next batch were in my locker. I could take them back to a 'returns' counter or leave everything I'd requested in my locker. (For future visits the first set of documents can be ordered from my kitchen table or wherever I have access to the web, ready for my arrival. Indeed a large part of the National Archives are catalogued for on-line search).

I asked for the documents suggested by Eleni Calligas, the young scholar who knows her way around these sources as well as anyone, an expert in Ionian politics and Hellenic nationalism:

I would suggest that the best place to look is the High Commissioner's Correspondence at the Colonial Office archive of the Protection, housed in the Public Record Office, now re-named National Archives but still held at the Kew. I would look at the last couple of years, from 1862 onwards - probably starting from CO136/177 to /184. If such a petition does exist and is signed by inhabitants of the village, it would be interesting to identify the local figure of importance, as the initiative probably emanated from there.

Five months before the British Protectorate ended

This does not really surprise me. I understand from Kostas and Thannassis that the two villages on Corfu, and another whose name I don't know, on Zakinthos, were opposed to enosis, and even today - so I read in May's edition of The Corfiot Magazine - of the island's eighteen bands, the philharmonic orchestras of Korakiana and Kinopiastes do not play at the celebrations of Unification Day held in Corfu each 21 May.

[A check on the Ano Korakiana website shows the Samaras Philharmonia Band was a definite presence in Corfu Town on 21 May, along with the three bands from Corfu Town - a reminder, as ever, to check sources! "Η Φιλαρμονική της Κορακιάνας που συμμετέχει κάθε χρόνο στην εκδήλωση αυτή, μαζί με τις τρεις Φιλαρμονικές της πόλης της Κέρκυρας, είχε μια πολύ καλή, ισορροπημένη και «δεμένη» μουσικά, παρουσία, κερδίζοντας τις εντυπώσεις, σύμφωνα με τα σχόλια που μπορούσε κανείς να ακούσει."]

It's possible the petition, if it was a petition on paper rather than a representation delivered orally to Sir Henry Knight Storks, has disappeared from the record, or was never allowed to appear on it. Given the profile of enthusiasm displayed for enosis and the denigration of pro-English sentiments reported by Sir Henry, it's possible that opposition was expressed more privately than support.

I shall search the Storks files again, and look also at Foreign Office files, but it may be that I need to go back to the extraordinary tenure at the High Commissioner's Palace of William Gladstone, over seven weeks between the 24 November 1858 and the 19 February 1859.** Perhaps it was during those weeks, before enosis seemed given, that the elders of Ano Korakiana and others delivered petitions against the ending of the Protectorate.

Such opinions may be unrealistic; they're still expressed, thus Harry Tsoukalas, a business man on the island, planning to stand in the 2009 EU elections in a week:

These things are anathema to say but the truth is that unification with Greece was the darkest day in our history. It was a huge mistake that we have regretted ever since.

In Chapter 2 of their book, Holland and Markides, report Gladstone visiting Athens as part of his Ionian mission. While there he sounded out Ionian and Greek politician on unification:

In a letter to the Duke of Newcastle, (scroll down on the link to '23.12.1862') Colonial Office Minister, in London, Sir Henry Storks includes a translation of an unsigned note in Greek found in Corfu Town:This analysis stressed 'a divided sentiment' in Greek thinking on the matter, so that union was 'feared as well as desired'. The desire sprang from a natural inclination to cohabit with fellow Hellenes; the fear from the prospect of incorporating a branch of their race whose competitive abilities and education were so finely honed. In sum, the Greeks of the kingdom were fearful that union would turn out to be 'an annexation of Greece to the Islands, not of the Island's to Greece. (p.32)

May the curses of St Spixidion(?)* light on him, who cries long live union with Greece.

Signature of Sir Henry Knight Storks, Lord High Commissioner of the Ionian Islands 1859-1863

*Note: Almost certainly St.Spyridon - Ἃγιος Σπυρίδων - Corfu's protective patron saint.

**Note: Harold Temperley (1937) in 'Documents Illustrating the Cession of the Ionian Islands to Greece, 1848-70', The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 9, No. 1, Mar., pp. 48-55, on p.49 describes three phases - covering at least 22 years - of the question of the ending of the British Protectorate:

A. Period of abortive proposals, 1848-65

I. Lord John Russell on possible cession to Austria, May 1, 1848 11. Palmerston on possible retention, December 21, 1850 111. Gladstone against annexation to England, February 2, 1855B. Gladstone's attempt at settlement as high commissioner extraordinary and its aftermath, 1858-61

IV. His views on prevalent misconceptions, March 22, 1861C. Period of cession and its aftermath, 1862-

V. Gladstone on the cabinet decision, December 8, 1862 VI. The queen's assent, December 9, 1862 VII. Clarendon in retrospect, March 15, 1870

'...not as Invaders, with views of conquest, but as Allies...'

The way the British and the Ionians parted company in 1864 is an exercise in the refined political delicacy with which a lose-lose, or at best a win-lose, situation can be turned into one that goes down in history, often to the bewilderment of those looking for a fight, as one in which almost all feel they've won, though quite a few, as Eleni Calligas observed of the Corfiot radicals, may be left bewildered. Such developments cannot be arrived at by one party to the potential conflict. The work of both, behind closed doors, is vital to the legerdemain of peaceful resolution. Apart from my particular interest in the mysterious petition from Ano Korakiana, this is why the peaceful and dignified conclusion of the Ionian Protectorate is of such enduring interest. In the records I was scanning on Wednesday I saw a translated slip passed to the Commissioner's desk in the last year of the Protectorate; 'If I my wife were pregnant with a child that I knew to be harbouring pro-English sentiments, I would rip it from her womb.' Storks notes receipt and makes no written comment.

* * *How did two parties, both of proven historical capacity for immeasurable blood-letting, end up on 21 May 1864 at the Port of Corfu, participating, against a background of jovial band music, in a joint ceremony, with bunting, flag waving, roaring salutes, bowing, hand shaking and smiles? It was the happy culmination of an exercise in political wisdom that benefits the English in Corfu to this day.

I conjecture that at the opening of the new Acropolis Museum in Athens on 20 June 2009 we shall witness - or, rather, not witness, because their machinations will be circumspect, circuitous and opaque - the prefatory manoeuvering of two politically cunning nations, as they finesse a way of speaking about the contentious issue of 'the marbles' that will eventually allow both parties to claim victory in conserving, maintaining, and restoring that ancient marmoreal commentary on the contest between Athena and Poseidon. Nationalists, kriegsliebers, keyboard warriors, from both sides, will grind their teeth in bewildered vexation, as the British and Greek flags unite, amid fireworks and mingled anthems, at a ceremony of many embraces and a thousand kisses, on a date to be agreed.

Dear Thanasis and Kostas. At last I got myself to the National Archives at Kew in London to search for any clues on that 'petition' from the village. It's been v.interesting but so far I have not found any document from Ano Korakiana or Kinopiastes. I have found many references though to the mixed feelings of people from the Ionian Islands - especially Corfu - about enosis in 1864. I plan to go back next week. If you have any further clues or advice do please pass this to me. Here is my diary with some images of my visit to to the Archives on Wednesday. Kindest regards. Xerete and wish me luck! Simon, Beaudesert Road, B20 3TG, UK

From: Κβκ Κορακιανα Date: Sun 31 May 2009 To: Simon Baddeley

Dear Simon. We are so glad to hear from you. Unfortunately we haven't had any clues so far but it's been very interesting for us to bring some references especially from Corfu. Thank you very much. We are looking forward to seeing you. Thanasis-Costas

Ionian Islands electoral lists ~ 1861 (Sta.Maura = Lefkadas)

Hi, thanks for that. It was always a tradition that Kinopiastes and Korakiana didn't go, but maybe that's changed. I'll amend it for next time! Hilary. PS Here is an archive article...

'Celebrating Union with Greece' Corfu News, Saturday, 15 May 1965:

In 1814 Great Britain, after a decision with the Great Powers of that time - Austria, Russia and France - established herself in the Ionian Islands as a ‘Protecting Power’. It was after the Napoleonic wars and the fall of the great Corsican, when the oppressive violence of the Holy Alliance was clouding the aged continent. A few years later liberating movements started in the whole of Europe. The revolution of 1821 gave the Greeks a conscience of their national rights and awakened into the souls of the enslaved the desire of freedom. The liberated Greek kingdom exercised an irresistible attraction to the people of the Ionian Islands. The French revolution of 1848 - which history considers as a starting point of the people’s spring - urged the Ionians to more vigorous claims. The first demands for a more liberal self-government formed, with the passing years, a strong national and social character. So, when in 1859 Gladstone was sent by the British government to the Ionian Islands to find a conciliatory solution, which would secure the continuation of the established regime of the Protectorate, the only voice he heard was ‘Union and only Union’. Four years later Great Britain was compelled to yield to the liberating struggle of the Ionians to accept the Union of the Septinsular State with Greece. On May 21 1864, the Greek flag was hoisted over the Citadel. Corfu and the six other Ionian Islands became an inseparable part of the independent Greek state.

To this Hilary added, from Corfiot News archives, this contemporary report on events on the island on 21 May 1864 - source not mentioned:

On the day of Union with Greece, British soldiers were exchanging military salutes with the Greek soldiers who had arrived to take over. When the Greek officer gave the order ‘Present Arms!’, one of the Corfiot spectators laughed and commented: ‘You hear that? These miserable Greeks have only just arrived, and already they’re begging!’ The Greek army was represented by some soldiers from the 10th Regiment, headed by General Pisa, who had been commanded to take over the island and its fortresses. As the British troops embarked into their warship and left, the general, together with the military and political leadership of the island, made his way to the Church of Saint Spiridon for a thanksgiving mass. Meanwhile, the common people were not so thankful. Under foreign rule for centuries, they now felt the time for revenge against the elite had come, and they lusted to pillage and burn the mansions of the landlords. And new authority was not yet in place. The people of Potamos, led by their political leader, Heimarios, set off for Town, advancing and shouting curses. Heimarios tried at first to calm them as he feared a confrontation with the army. But finding that impossible, he tried to persuade them to head for the countryside. ‘That’s where the big fight will be!’ he promised. But the most hot-blooded would not listen. They reached Platytera, where the Maltese community lived, and attacked the gardens and fields and smallholdings of the workers of that poor area. Heimarios could not stop them. But then he shrugged and said to himself: ‘Well, let them get on with it. Let them work off their anger on the Maltese, who have no mansions. The worst they can do is beat up a few locals, and steal a goat or two, and they’ll be happy. When we get back to the village, they’ll have calmed down and we can give the animals back.’ The Maltese men were absent, and only old people and children were at home. The Potamites did not harm them. They untied the sheep and cows, herded the grazing sheep, set fire to some thatches, and returned with their grand spoils to Potamos. They entered the village singing in celebration. But at the outskirts, they were brought up short by screams coming from their own houses. While they had themselves been looting, the men of Kontokali, returning in a gang from Town, had put into action a long-held plan to attack Potamos as soon as the British left. They entered the village from the east, causing the women and children to flee. Then they beat up a few remaining men, barged into the houses, and looted everything they could lay their hands on. After the initial shock at finding them there, the men of Potamos struck back, and the gang from Kontokali, caught in the surprise attack, fled down the hill. It was a remarkable sight - the Kontokalites fleeing with their booty, chased by the furious Potamites. But the runaways were weighed down with their loot, so as they ran they were the shedding clothes, tools and household goods they had stolen. The men of Potamos chased them as far as the outskirts of Kontokali. Spiros Peroulakis, a shoemaker from Potamos, was an eye-witness to the mayhem. It was a spectacle that rendered him speechless. The whole scene was a seething battleground, a mass of bodies - men, women and children - struggling against each other with scythes and spades. Meanwhile, two villagers from Korakiana appeared, running with sweat and panting fit to burst. They entered the kafenion where Peroulakis had taken refuge. ‘Give us water!’ they demanded. ‘We’re dying of thirst!’ ‘What are you running for?’ asked Peroulakis. They told him that they were on their way to Town to report to the army that Korakiana was being attacked by a group of about two hundred men from Skripero. At first, Peroulakis was under the impression that they were pillaging the houses of the landlords, but the men told him that they were looting the common houses, stealing oil and wine, and breaking into dowry chests. ‘Why don’t you call on your own men to protect their houses?’ asked Peroulakis. ‘We tried,’ was the reply, ‘but they were too busy looting in Skripero!’ And that is how the Union of the Ionian Islands was celebrated in Corfu’s villages.

No comments:

Post a Comment